BY BLAISE UDUNZE

It is a sobering reality that one South African bank, Standard Bank Group, has a market capitalisation of roughly ZAR 384.34 billion (about $21-22 billion), while the entire Nigerian banking sector combined cannot match it. For a nation of more than 200 million people, with an economy that should be the beating heart of Africa, the fact that a single Johannesburg-based bank can outweigh the collective worth of Nigeria’s 33 licensed banks is more than embarrassing; it is scandalous.

This disparity is not just about prestige. It is about the fundamental ability of Nigeria’s banking system to mobilise capital, finance development, and command investor trust. The comparison with South Africa, a country with less than one-third of Nigeria’s population and a smaller GDP in nominal terms, lays bare the structural weaknesses that have crippled Nigerian banks for decades.

As of May 2025, Nigerian banks listed on the Nigerian Exchange (NGX) had a combined market capitalisation of about N10.5 trillion. In dollar terms, depending on the exchange rate benchmark, this amounts to less than $8 billion. That is the total value investors are willing to place on the entire Nigerian banking system.

By contrast, South Africa’s top six banks together are valued at more than $70 billion. Individually, Standard Bank alone commands a market cap of around $21.8 billion, while FirstRand hovers at about $20.5 billion. Absa, Nedbank, and Investec all sit comfortably in the multi-billion-dollar bracket.

In Nigeria, the biggest player, GTCO, is valued at less than $2 billion, barely a fraction of its South African peers. Access Holdings, despite boasting assets above N32 trillion ($71 billion), trades at a market cap of just about $710 million. The disconnect between asset size and market value speaks volumes about investor distrust, weak governance, and systemic fragility.

The paradox of Nigeria’s banking industry is that on paper it appears profitable, yet in reality it is fragile. In 2024, the top five lenders declared after-tax profits that surged more than 270 percent year-on-year. But by the first quarter of 2025, that growth had evaporated, slowing to a meager 0.74 percent.

The supposed windfall profits were largely a mirage created by the naira’s freefall, which inflated the value of foreign currency holdings on paper.These were not profits born of efficiency, innovation, or stronger lending; they were accounting artifacts.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), seeing the danger, stepped in to block banks from paying out these revaluation gains as dividends, insisting they be held as buffers against future shocks. That intervention exposed the hollowness of the profit’s narrative.

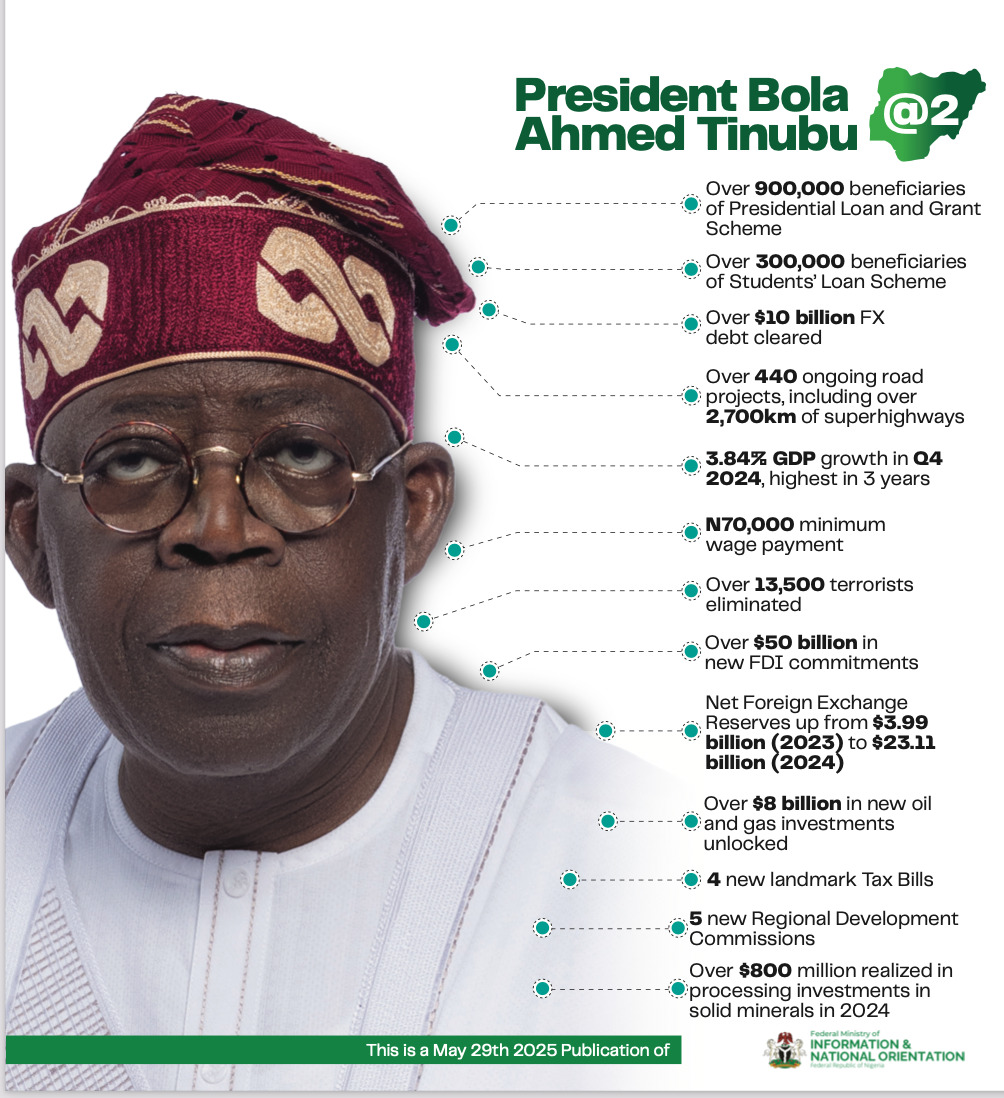

The recapitalisation push is the clearest sign yet of the sector’s fragility. With six months to the March 31, 2026, deadline, the CBN has confirmed that fourteen banks have so far scaled the recapitalisation hurdle. The governor of the CBN, Olayemi Cardoso, disclosed this on Tuesday, September 23, 2025, during the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting in Abuja. That leaves nearly 19 banks still scrambling to raise funds in a market already skeptical of their true value.

If Nigeria’s banks were genuinely as profitable and resilient as they claimed, they would not be racing to the capital markets, scrambling for fresh equity to meet the CBN’s new recapitalisation thresholds: N500 billion for international banks, N200 billion for national banks, and N50 billion for regional players. The contradiction is stark, record profits on one hand, desperate fundraising on the other.

The currency crisis further underscores the fragility of Nigeria’s financial system. According to the Forbes currency calculator report for September 2025, the naira has been ranked as the ninth weakest currency in Africa, trading at about N1,487 to the dollar. The ranking, based on real-time foreign exchange market data, captures how demand and supply, investor sentiment, and broader economic conditions have battered Nigeria’s exchange rate.

On the continent, only currencies like the São Tomé & Príncipe Dobra, Sierra Leonean Leone, Guinean Franc, and a handful of others fare worse. By contrast, the Tunisian Dinar, Libyan Dinar, Moroccan Dirham, Ghanaian Cedi, and Botswanan Pula sit at the top as Africa’s strongest currencies. For Nigeria, the supposed giant of Africa, such a lowly placement is telling.

It is not just a technical matter of exchange rates; it is a reflection of waning investor confidence, policy inconsistency, and the erosion of the naira’s credibility. And this credibility gap feeds directly into why Nigerian banks are so poorly valued compared to their peers.

This is not the first time Nigerian banks have faced such a reckoning. In 2004-2005, then CBN Governor Charles Soludo spearheaded a bold consolidation exercise that shook the industry to its foundations.

At the time, Nigeria had eighty-nine banks, most of them undercapitalised, fragile, and unable to finance large-scale projects. Soludo raised the minimum capital base from N2 billion to N25 billion, forcing mergers and acquisitions that reduced the number of banks to 25 by 2005.

The exercise created bigger, more competitive players like Zenith, GTBank, Access, and UBA, which for a time stood tall on the continental stage. Nigerian banks expanded across Africa, rode the wave of oil-driven economic growth, and built reputations as ambitious challengers to South African dominance.

But the momentum did not last. The global financial crisis of 2008, compounded by oil price volatility and weak regulatory oversight, exposed vulnerabilities. Many banks were overexposed to the stock market and the oil sector.

By 2009, a new CBN governor, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, had to intervene with another round of reforms, including emergency bailouts, leadership changes, and tighter risk management rules. While those measures stabilised the sector, they also clipped its wings, pushing banks towards conservatism rather than innovation.

Over the next decade, as South African banks deepened their continental footprint and attracted global investors, Nigerian banks retreated into a survival mode, relying more on government securities, forex arbitrage, and fee-based income than on transformative lending.

Today, the consequences are clear. Investors are not rewarding Nigerian banks with higher valuations because they see deeper issues: weak governance, currency instability, short-termism, and a preference for rent-seeking over risk-taking. Access Bank, with assets of over $71 billion, is valued by the market at less than $1 billion, which is an absurd disparity that reflects not just naira devaluation but also a crisis of confidence.

Meanwhile, Standard Bank and FirstRand are rewarded with valuations in the tens of billions because they have built reputations for governance, stability, and consistent growth, even in a difficult South African economy.

The implications of this disparity go far beyond balance sheets. Banking is the lifeblood of any economy. Without robust, well-capitalised banks, Nigeria cannot fund the infrastructure, industrialisation, and job creation it desperately needs. Instead of driving development, banks have become rent-seekers, charging high fees, exploiting exchange rate gaps, and surviving on government bond yields.

This is not banking for growth; it is banking for survival. The danger is that Nigeria’s banking sector could become increasingly irrelevant on the continental stage.

Already, pan-African conversations about finance, trade, and fintech leadership are dominated by South African, Kenyan, and Moroccan institutions. If Nigerian banks cannot scale up, innovate, and command investor trust, the country risks losing its voice in shaping Africa’s financial future.

Fixing Nigeria’s banking woes will require bold reforms, not half measures. Deep recapitalisation is essential, not just to meet regulatory minimums but to build genuine resilience. Governance must be overhauled to eliminate opacity, insider abuses, and regulatory capture.

Banks must be compelled to shift their focus from government securities and currency speculation to financing manufacturing, SMEs, and infrastructure, which are the engines of real growth. Macroeconomic stability, especially currency and inflation control, is indispensable to restoring confidence.

And if that means forcing consolidation once again, so be it. Nigeria does not need 33 weak banks; it needs fewer, stronger institutions that can compete with global peers.

Nigeria prides itself as the giant of Africa. But in banking, it is dwarfed by a smaller neighbour. That a single South African bank is worth more than the entire Nigerian banking system should serve as a blaring siren. It is a sign that the foundations of Nigeria’s financial architecture are weak, and without urgent reform, the gap will only widen.

The lesson is clear: size of population or GDP counts for little if banks cannot mobilise and protect capital.

Until Nigeria’s lenders transform from fragile, short-term operators into robust, trusted financial powerhouses, the humiliation will persist with one South African bank towering over an entire Nigerian industry.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional writes from Lagos, can be reached via: blaise.udunze@gmail.com