By Abdullateef Ishowo

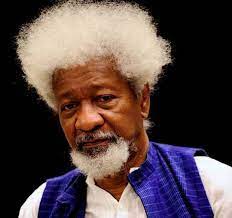

Tuesday,13th July 2021,marks the 87th birth-date of the Kongi, the Irunmonle of African literature, Professor Wole Soyinka; and it wasn’t surprising that he was celebrated across the globe. I flipped through pages of virtually all Nigerian dailies yesterday as his face dominated all and concluded that this man is much more influential and far well appreciated across the globe than any dead or living Nigerian ruler.

People of Wole Soyinka’s type, pedigree and intelligence are quite rare. He’s eighty-seven brilliant men in one. If Wole splits to eighty-seven segments, each of them will still qualify as being regarded as brilliant. I think he’s specially made by the creator. When a goldsmith makes a special hoe that looks more beautiful than many others he had made, he feels happy. Hold me for it if you like; though a pagan, he’s one of the living prides of the creator. When you look at him, you are left with no choice than to acknowledge and appreciate the fact that all wisdom comes from the Lord, the creator.

Wole Soyinka, perhaps, is one of the most misunderstood, exceedingly controversial, unnecessarily and ‘fiercely individualistic’, exceptionally gifted and radically ideological Nigerians in public and literary life. This rounded literary artist of Ìjègbá extraction is thus a living literary idol who has romanticized with all literary types (poetry, prose and most importantly drama).

Among his numerous plays, “The Trials of Brother Jero and Jero’s Metamorphosis” where he used Pastor Jeroboam as the ungodly man of God transiting from poverty to affluence through deceit, hypocrisy and the natural endowment of tongue of fire, has always been my companion; as the play depicts the very happenings in our society today.

The inter-cultural marriage ceremony he conducted between English and Yoruba language in ‘Ake: Eleven Years of Childhood’ forced Oxford Dictionary to accommodate some Yoruba words to its recent editions. In his prison notes, “The Man Died” and “The Interpreters” (both prose), he displayed his power of language. I read the former about three times before I could grasp what he meant by ‘the man died’ while the situation was worse in the latter. Up till now, I can’t really fathom what Soyinka meant by ‘the interpreters’. I got frustrated and had to dump the provocative novel even before reading up to 1/10 of the book.

You may want to ask why he had to write such a book, he simply once told a BBC interviewer, “I was writing naturally”. But if I must answer you, that is what makes Soyinka thick and distinguishes him from all other African writers. After all, there are several other simpler ones you can lay your hands on.

Soyinka occupies his distinct place within the ‘quartet’ on account of his propensity for taking very daring artistic and political risks in furtherance of his deepest political and ethical convictions, risks which often entailed considerable peril to himself and also profoundly challenged, but at the same time complexly re-inscribed the determinate elitism of his generation of writers. The articulation between the political and artistic risks is one of the most fascinating and complex aspects of Soyinka’s career”.

To his critics, he simply quipped, “A tiger does not proclaim his tigritude, he pounces”. In other words: a tiger does not stand in the forest and say: “I am a tiger”. When you pass where the tiger has walked before, you see the skeleton of the duiker, you know that some tigritude has emanated there.

Happy birth-date, Oluwole Akinwande Soyinka – the ‘Ogbuefi’ and ‘Ashiwaju’ of African Literature.